Ed. Note: Here are the wonderful words my brother Gary wrote and delivered at Dad’s funeral.

Dad was so many different things to each of us that I will not try to mention them all. I just want to recall some of what he was for me while I was growing up as his oldest son, and perhaps remind you of how he affected you and your life.

A few days ago, Sherry remarked on the fact that, when she and Ray go hiking in· the Cascades along the Santiam River, they are almost certainly hiking on trails that Dad constructed during his CCC and Forest Service days. And that reminded me that, in my earliest memories, Dad was always the one who made things–and fixed things–with his hands, with his tools, and with the things he said. When I was about 5 years old, he made big murals on my bedroom walls–a cowboy on a bucking bronco, an Indian chief, a wagon train crossing the prairie. Below the murals, along one wall, there was a big sheet of plywood fastened like a table to the wall, where my electric train was set up. The tracks ran around the table, through a tunnel in a mountain, then past a water tank with a boom and spout I could lower with a little chain, and then a red brick depot with shrubs around it. I remember Dad making the mountain and its tunnel out of papier mache, and the water tower out of a small Crisco can, which he soldered onto some scrap metal for legs. To make the depot, he cut up a Folders coffee can and straightened it out and soldered it back together, and then painted it brick red–he put sand in the paint to give it texture–and he made the shrubs out of steel wool painted green.

In those days, when I woke up in my room, I was in the middle of a little world that Dad had made for me with his own hands.

He made things for all of us–Stick horses for Craig and Kirk, handsome wooden beasts to replace the lamentably inadequate makeshift ponies they rode. Craig rode a broomstick, I think, but poor Kirk didn’t even have a stick at all. He rode a short piece of rope. I can never remember whether it was the broomstick or the rope that was named Prigger. And he made penny banks for each of us, made them out of coffee cans cut up and soldered together and painted with fancy pictures. Dad and Mom drank a lot of coffee in those days. And for Lisa and Kim’s dolls, he made wooden cradles that Mom decorated with folk designs she found in a library book; and later he made a doll house for them, an exact replica of the house itself, complete with lights that worked. A flashlight bulb inside a ping pong ball hanging from the cathedral ceiling–just like the spherical white hanging fixture in the real house. And bunk beds with desks underneath for Craig and Kirk, and coffee tables and television consoles and kitchen cabinets for the house. And concrete patios and wooden decks and landscaping. (Ed. note: And a figure-eight goldfish pond with a fountain, embedded with rocks he had collected and polished!)

And at Christmas time Dad would buy a tall tree for the living room, get it home and look at its oddities of shape and stance, and then get out a saw and a drill and rebuild it – sawing off limbs and drilling holes in new places and sticking them in, until it was a new tree.

And we decorated it with ornaments that Dad had designed and made-cutting up coffee cans, of course, and painting them and sprinkling glitter on them, and folding them until they became bells and Santas and angels and such.

So when we came into the living room on Christmas morning, we found a Christmas tree that Dad had made, decorated with ornaments he had made, and a lot of presents that Dad had made.

Among my early memories is this one: At the Veda’s place in Jennings Lodge (Ed. note: we named our houses after the landlord). I wake up late at night and go downstairs to the bathroom, and Dad is sitting in the kitchen, poring over some Heathkit diagrams, soldering resistors and capacitors and such. He was taking classes in television and radio repair, and he needed instruments, so he was building an oscilloscope.

When we first moved to Jennings Lodge, he sent away for Department of Agriculture pamphlets on raising chickens and rabbits, and with their advice he built chicken coops and rabbit hutches out of scrap materials he found in the barn in Jennings Lodge. They were made of scrap lumber, not quite what the pamphlets specified, so he apologized and said they were only temporary. But of course they were still standing when we moved away years later. And in front of the house, across the lane, he made a huge garden. -We didn’t have a tractor, so he had to drag the ancient harrow behind our big black square 1939 Chevrolet – I can still see him bouncing in the front seat of the car as it lurched and lunged across the ground, smoothing it out so he could plant peas and beans and corn and potatoes.

And so as we were growing up, we were continually walking out into a world that Dad had made for us–gardens and barns and patios and landscapes that we had watched him build.

At some point he began to go prospecting during his vacations, looking for lost gold claims and the Blue Bucket Mine – if he found them he never told us – but eventually he found some peculiar rocks in southern Oregon and spent a winter or two studying geology until he was certain they were jade. So he staked a claim and went down there and dragged boulders out of the wilderness using cables and winches that Lisa swears he made himself out of coffee cans, and then bringing them home and tearing apart a washing machine for its gears and motor, and commandeering some bicycle wheels until he had made a saw that would cut the stone. And then learning the ancient craft of lost wax metal casting and making rings for everyone in the family.

So on my hand I wear a jade ring my father made for me.

When manufactured things wore out or broke down, he usually did not buy replacements even when they were available and cheap. He preferred to rebuild them, making the necessary parts himself. I have watched him rebuild broken gears on a washing machine-drawing a template and making some kind of mold and melting some metal (was it coffee cans?) and pouring it into place and filing the teeth to the right size and shape. Lisa has watched him make a fuse for her television–not out of coffee cans, but out of a light bulb and some aluminum foil.

When he fixed such things or made such things, he almost always said that they were only temporary. But I don’t remember any of his contraptions wearing out. They’re still out there somewhere, I suppose, still working.

When he wasn’t making temporary replacements that lasted forever, he was often working on some highly improbable dream. I remember him in the basement in West Linn, fiddling with some magnets and motors and wire, trying to make a perpetual motion machine. It would have no practical value, of course, but he thought he understood how to do it, and so he was trying to do it. I asked him about it, and he explained how one magnet could be suspended without friction in the magnetic fields of two others, and a motor would turn the suspended magnet in such a way that a current would be generated in its coils, and the current would turn the motor, generating more current. Forever. I could clearly see that it SHOULD work. He never got it exactly right, but in principle, he understood it and explained it to me.

He also invented other devices–one that would attach to the car’s carburetor and add a spritz of water, and make it run better. He had noticed that the car ran better on rainy days, and so this device was a way of creating that damp air right in the motor. And he showed us how to build a yellow jacket trap, which we never got around to producing but which someone else also figured out and is now making for profit. The best thing about those inventions was not so much the device itself as his explanations of the principles behind them. Explanations of how things work and of how things OUGHT to work were another of the great things he made for us.

Often his explanations contained more information than we wanted, or more than we could absorb, or maybe even not quite what we asked about. When he built those rabbit hutches and got some rabbits and mated them, he invited me to watch. And while the rabbits were–engaged–he was saying something about how male genitalia are external and female genitalia are internal, and I was scarcely listening at all because the rabbits were acting extremely weird and I wanted to know about THAT.

But he could explain anything. Even when he didn’t know the explanation, he’d hazard a guess. We’d ask him why the sky is blue and rain clouds are black and he’d say “I don’t think even Leonardo da Vinci figured that out, but let’s see. The specific gravity of the clouds should be about 1, and the atomic weight of oxygen is 16, so … ” and we’d have no idea whether it was right or not, but it sounded right. And partly because of those explanations, I awake every day in a world that seems explainable, a world that even I might be able to figure out.

And besides making things out of coffee cans and explanations out of thin air, he made music and songs on the guitar and the banjo and the fiddle and the harmonica and the concertina. And he made lots of paintings for our walls. And he made poems about life itself and about his children. And he made stories. Millions of stories, most of them just like his explanations–maybe they weren’t quite true, but they should have been true, and after he had told them a few times they were true. Stories about growing up in the Cascades with his brother Bob, or about working with Bob in the Wyoming oil fields, welding storage tanks and getting arrested because someone thought they were escaped convicts–the notorious Jones Brothers. When the two of them got together and traded stories the house would rock with laughter all night long. He told us stories about things that happened before we were born, stories about things we had seen him do, stories about things we ourselves had said and done. Even when we remembered the event itself, the stories Dad told about them made our lives more interesting, more funny, more rich and meaningful–and more permanent. Some things are not made simply out of coffee cans, but also out of love.

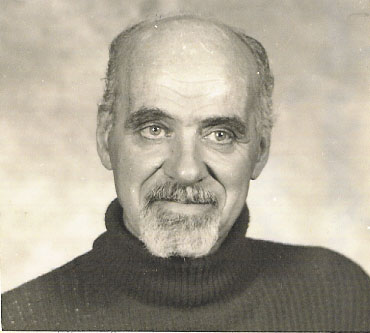

(Ed. note: I think the photo above is the one he used for his passport. It’s how he looked for the last twenty years of his life, and the face I see in my dreams.)

re naming our rented homes for the owners–the Jennings Lodge place was owned by Mr. and Mrs. Vitas–he was an immigrant from Yugoslavia, and entirely down-romish. She was a social climber who was hated by one of our turkeys.

LikeLike